Prof. Dr. Vytis Jurkonis is the Director of the Freedom House Vilnius office, where he spearheads projects focused on democracy, human rights, and civil society in the Eastern Partnership region and beyond. Since 2006, he has also been a lecturer at the Institute of International Relations and Political Science at Vilnius University, sharing his expertise with students and scholars.

Renowned for his in-depth knowledge of Belarus, the Eastern Partnership region, Russia, and Lithuanian foreign policy, Dr. Jurkonis has made significant contributions to understanding and addressing the challenges these areas face. His professional endeavors extend beyond academia and policy research, encompassing on-the-ground experience through fact-finding missions and training sessions for civil society activists and human rights defenders in countries including Afghanistan, Burma, Cuba, Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine.

Before joining Freedom House, Dr. Jurkonis led the Policy Analysis and Research Division at the Eastern European Studies Centre, a prominent think tank based in Vilnius. He also served as a national researcher for the European Foreign Policy Scorecard, a project by the European Council on Foreign Relations that evaluates EU member states’ engagement with global and regional challenges.

A participant in the U.S. State Department’s prestigious International Visitor Leadership Program, Dr. Jurkonis has further enriched his understanding of global human rights issues through academic achievements, including an expert diploma from the Institute of Human Rights at the Law Faculty of the Complutense University in Madrid.

With his extensive experience in both scholarly research and practical fieldwork, Dr. Jurkonis remains a respected figure in international relations, human rights, and policy analysis.

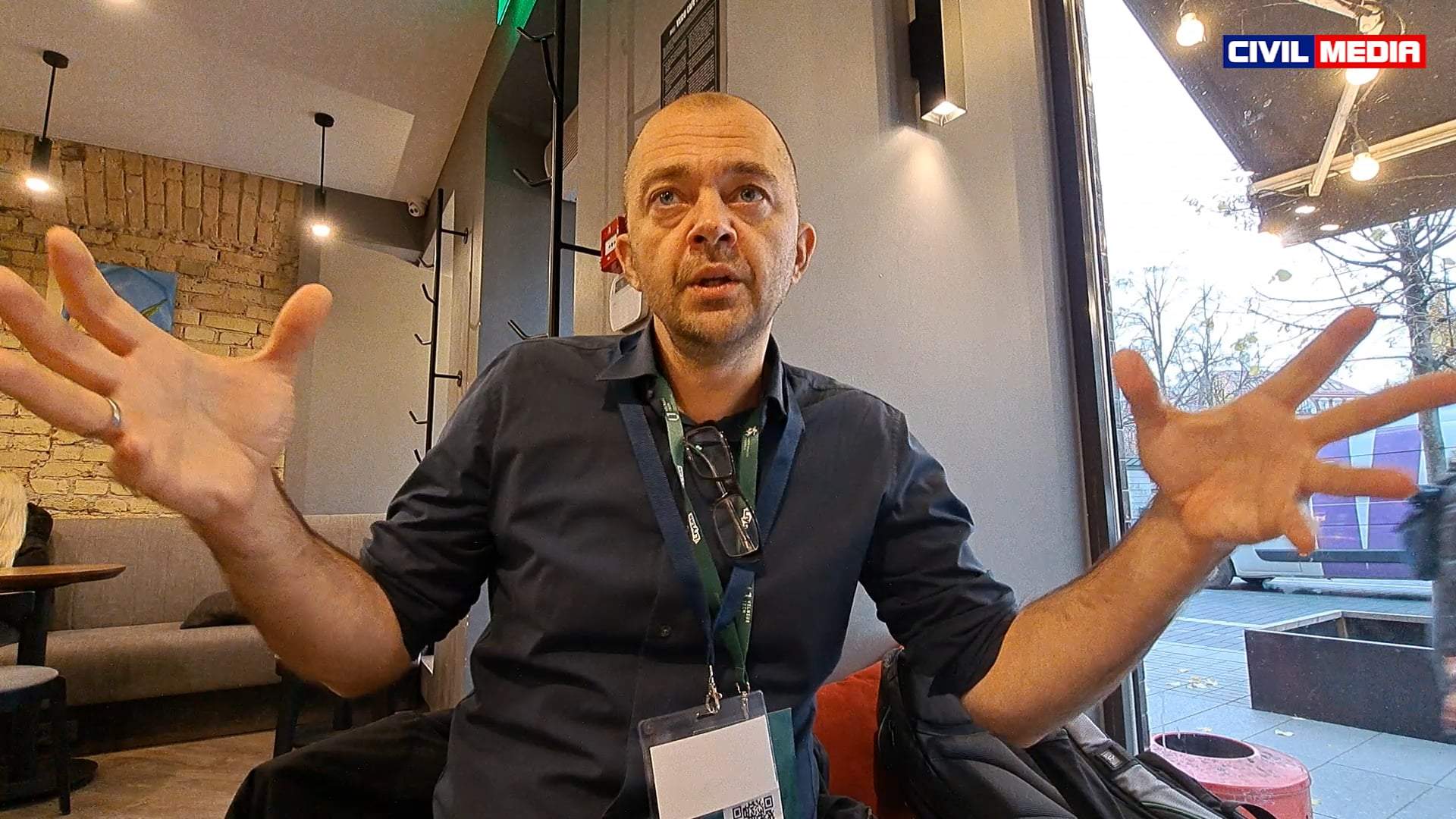

We had the privilege of meeting Prof. Dr. Vytis Jurkonis at the High-Level Forum Against Authoritarianism – Future of Democracy, held in Vilnius on November 7-8. Organized by Lithuania’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the event brought together a distinguished group of politicians, diplomats, and MPs from across the globe. Notable participants included Lithuania’s Foreign Minister, Gabrielius Landsbergis; Head of the Community of Democracies, Mantas Adomėnas; Armenia’s National Security Council Secretary, Armen Grigoryan; EU Special Representative for Human Rights, Eamon Gilmore; Polish Senate Deputy Marshal, Michał Kamiński; and members of Ukraine’s Verkhovna Rada.

XHABIR DERALLA: I’m speaking to professor Vytis Jurkonis, who teaches Political Science and International Relations at the University of Vilnius, and I would like to start off with a question of the Lithuanian persistent support of the Ukrainian fight for freedom against the Russian aggression. What it is like to be in Lithuania, being almost on the borders with Belarus, which is practically at war with Ukraine, as an ally of Russia, and being on the border of Kaliningrad, which is the territory of the Russian Federation. How is it? What is the situation now, especially in the light of the latest developments on the world stage, including the United States elections?

VYTIS JURKONIS: Well, there are a few points. One point is that we need to continue to support Ukraine, make sure that it is able not only to defend and win this war, because this war staged against Ukraine is against the international law and regulations, it’s an invasion without any justification whatsoever. And of course it’s not only the military casualties, but the Russians and the Kremlin is bombarding the civilian infrastructure, entire towns of Ukraine are wiped out, and, of course, Ukraine is a dear friend. Lithuania is in touch at multiple levels, governmental, parliamentary level, at the level of civil society, people to people, academic expertise, you name it. There is some common history with the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, where like Ukraine, Lithuania was in a joint state at some point. So, there are many historical, emotional, neighborly attitudes.

Currently, we have a huge wave of solidarity, civic initiatives – collecting money, goods – trucks sending all that to Ukraine, to the Ukrainians. Previously, when the full-scale invasion started, we were doing a lot of evacuations, Ukrainian people, almost 100,000 of them ended up in Lithuania. Lithuanian citizens were giving their homes, my own parents were giving one bedroom in their apartment to two Ukrainian women with kids, who were sheltered for almost a year. This solidarity is overwhelming. You can see that in Vilnius there are plenty of Ukrainian flags. Sometimes you feel like you are in Ukraine. Even President Zelensky, during one of his visits, I think during the NATO Summit in Vilnius, came and he said “I feel like home.”

But it’s not only a thing of empathy, it’s also a very serious thing, because Lithuania understands what it’s like to live nearby an aggressive neighbor, right there nearby, like Kremlin, Russia. We have, as you mentioned, Kaliningrad border, which is heavily militarized, plus we have Belarus, where the Wagner army soldiers were deployed, where there are talks and rumors about nuclear weapons being deployed.

It’s not only the issue of the February 2022 full-scale invasion. Lithuania was warning the Euro-Atlantic community about the potential aggression of the Kremlin way before, even before the Crimean Annexation in 2014, before the war in Georgia in 2008.

Let’s remember that in 2007, there was a story of the bronze soldier in Tallinn, where because of the removal of the Soviet monument, suddenly Estonia was hit by a number of cyber-attacks. There were some youth groups smashing windows, rioting and all that, which is a hybrid attack. So, in a way, the green men started not in Crimea, but back then in 2007. Lithuania was sometimes called [dismissed], like “oh they are too emotional, too sensitive regarding the Soviet past.” But, in fact, then when 2008 happened, there was a wake-up call for some countries. They said maybe Lithuanians and the Baltics have something to say on the matter.

And then, when 2014 happened, they said “yes, maybe the Kremlin is a bad player, maybe we shouldn’t trust them that much.” And then this unimaginable in the 21st century, full-scale invasion, bombardments on peaceful society is happening, with millions of Ukrainians fleeing their homes, I think that was the wake-up call, that we need to review the entire cooperation with Russia. I mean, plus, we also need to admit Lithuania was very often called, I mean, accused by the Kremlin, as if being Russophobic, that kind of propaganda thing for them.

But, one, Lithuania is not Russophobic, first, because we are not afraid of Russia. We are a respected Euro-Atlantic community member, that’s one, we are proud of our history, we know what it is to resist the Soviet occupation, I mean we have that in our history, fighting back under very severe conditions. Number two, we are not Russophobic, because we don’t have anything against Russians. Our problem is Kremlin and Putin and this criminal regime, which is also not only bombarding Ukrainians, not only interfering into all sorts of domestic affairs, be it in the Balkans, be it in Europe, be it in the United States, but also it is oppressing its own population.

You know of a number of political prisoners, you know of some opposition people who were assassinated, poisoned, assassinated and killed eventually, including independent journalists. So, this criminal regime is not accountable to its own people, it’s actually punishing its own people, and you know and you’ve seen in the conference that you are attending, that there are a number of Russian and Belarusian dissidents who found shelter in Lithuania, which only means that Lithuania has nothing against the Russian people or the Belarusian people, but we have a lot against the authoritarian regimes, which are trying to create chaos in international institutions and generally in Europe.

DERALLA: In the debates across Europe, including thе High Level Forum Against Authoritarianism – Future of Democracy, hosted by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Lithuania, we are seeing a lot of doubts and also a great deal of dilemma: What is to be done in order to defend the democratic processes, the democracy across Europe, and across the world. It seems that there are too many assessments, but not so many solutions offered.

Can we actually go back to the point when the Lithuanian government and the intellectual elite and the experts of Lithuania were warning the West, the Euro-Atlantic community of the growing danger from the Kremlin. The response back then was weak and meek, and almost non-existent.

Maybe we can find some ways to find solutions exactly at this moment, when the Euro-Atlantic community decided not to be asleep ahead of the growing danger and maybe we could think of starting from there. What would be the solution?

Let’s put it clear and short: What would be the solution for defeating the growing danger of the authoritarian regimes and the dictatorial militant regime of the Kremlin?

JURKONIS: Well, one is the immediate thing, which is we need to support Ukraine. We understand that there are gross human rights violations. It’s a war crime that is happening there. We see the population being raped and all of that. So, the question is – what the hell is the United Nations doing about that!? Which is here to provide security and all of that. But that is a more long-term thing to fix our international system and the international institutions. The other long-term thing, if we are not talking about the immediate supply of weapons to Ukraine and helping them to defend themselves – is to make sure that we are confident. We go back to the very roots and the foundations of what Europe is. And Europe is about freedom, democracy and human rights.

I think that, at some point, many Europeans became lazy. They take human rights for granted, that it’s going to be for ages and ages. And even with the elections in the United States recently, we see that not all is well with the health of our own democracies as such. Make no mistake, it’s not like someone is going to be lecturing about democracy. We need to also fix our system from within. But we also need to admit that democracy cannot be taken for granted. That we need to defend it, protect it, fight for it when needed. So, in this regard, I also think that democracy and human rights would be at the forefront of our foreign affairs or the foreign affairs of the Euro-Atlantic community.

At some point, after this big bang of the expansion of the EU in 2004, we kind of had this Fukoyamish type of thinking “end of history”, that it’s like everything changed and everything is going to be good, all right, rainbows and butterflies.

DERALLA: Yes, and there was this statement of the Russian dictator Putin at the Munich conference [2007] when he said that maybe the next summit of NATO should be held in Moscow, and you saw smiles and everything there.

JURKONIS: So, there was some naivety, if you will.

DERALLA: Was it naivety only, or maybe also protection of the elites’ interests?

JURKONIS: Yes, I think that the answer is complex here. One thing which we need to admit, and this is a big, big conversation to have with our own populations. There’s nothing that is for free. There’s nothing in the world that is cheap. There’s no cheap oil, there’s no cheap gas. If you have cheap oil and gas, somewhere there’s exploitation of nature, devastation of the natural resources and there are no cheap goods.

Talk about China, if there are cheap goods, most probably we are talking about some sort of modern slavery where these cheap goods are. Someone is exploited. So, I think that we need to understand that whoever has worked himself with their own bare hands, like in the garden, knows how much it takes to grow a plant, grow a tree and all of that.

DERALLA: Being a Professor of International Relations and Political Systems, you probably understand the relation between economics and politics, and the cheap gas and oil actually goes within certain messages and certain strings that are being delivered in those economic or trade packages. And especially if we speak about the economic and trade relations between countries such as Russia or China or others like that – they usually are quite corruptive. Having state control by a very narrow circle of people – they somehow manage to get to the leaders, to get to the key decision making structures and corrupt them. And actually those cheap oil and gas deals are – in the end – very expensive.

JURKONIS: Oh, absolutely.

DERALLA: Okay. They make a few people very rich, but then they strip the society from stability, from its own peace.

JURKONIS: Well, you know, the way the Kremlin was treating the three Baltic countries, there was kind of a joke that it’s like spoiling one, being in constant conflict with the other and neutral with the third and always rotating that. So, Lithuania has set a goal that we need to become energy independent from Russia. And that has been tough. In the short-term we paid a higher price and there were always voices like – why can’t we simply buy stuff which is cheaper, why make the Kremlin angry.

But what we wanted in the long-term, to be independent of any sorts of blackmail, which we have witnessed before, like in 2022 when Russia was blackmailing many, many European countries because no matter how rich, we became so dependent, we became hostage of that. And we need to understand that we are not against business, economy, cooperation and all of that, but it needs to rely on certain standards. It needs transparency and all of that. And my former boss used to say that, you know, what is Russia’s biggest export? It’s not oil. It’s not gas. It’s corruption. So, you know, these kleptocratic ties and all of that relying.

So, we need to admit that in this regard there are actually people within our societies, who are politicians, who are agents of that malign influence, who have a lot of money and can also buy media or spread disinformation. So, all of that is happening, therefore, there is no one-silver-bullet-solution. You cannot only fix something within the media field or you can fix something with the anti-corruption agency. And at the same time, people are at a stage – why bother?

This is so difficult, so complex. We need to say that democracy is about constant work, constant defense, constant engagement. And obviously, you can be a bystander, a free rider, but in fact, healthy democracy is where you are not only talking about the rights, but also about the responsibilities and that you need to engage.

Therefore, we need active civil society, we need partnership between the government and civil society, we need watchdogs, we need investigative journalism to investigate the malpractices and the governments need to be not defensive, but responsive to that kind of stuff. Otherwise, we might be in a very vulnerable position, because after all, no matter how rich the Kremlin is, no matter how much unaccounted money they have, they cannot buy them all. They usually rely on the very few people who have some power. And democracy is not about one person, it’s about the bottom-up pressure.

Therefore, even from the standpoint of a young democracy or transitional country, the solution is to rely on people. And this is the tragedy of the very same neighboring country, which is when Lukashenko, the authoritarian leader of Belarus was saying – I’m the guarantor of the sovereignty, of the independence and all of that – no, you are the problem because the entire country is becoming a hostage of your own personal power grip, if you don’t trust the society, if you don’t trust the institutions.

DERALLA: At the end of the day, Lukashenko goes to his office armed with an AK-47, which tells a lot about how trusting and trustworthy this guy is.

JURKONIS: The bottom line is for us ourselves to answer, is democracy a good thing? I mean – is democracy a thing that we want to live in, if we want responsible and accountable governments? We are daydreaming because as I’ve said, it requires responsibility. And what the Kremlin is trying to and other autocrats are trying to pursue is that democracy is weak, democracy is chaos, and they are seeding this chaos everywhere. Therefore, people sometimes are willing to have a strong hand, you know, a strong politician and authoritarian, some sort of trend, because the vertical power makes fast decisions.

But in a way, like if we talk about the Euro-Atlantic community, the very fact that we need to come to an agreement between the 30 countries, you know, we have a more sustainable solution. I mean, yes, we are impatient, we want very quick decisions, but not necessarily these quick decisions are going to be sustainable. That said, we also need to look to the other side. How are the autocrats or the Kremlin doing? I think they are not doing great. You know why? Because they are unable to create anything, anything sustainable. What they can do is to mess around, and destroy. So, there’s nothing positive.

DERALLA: But then we come to the very alarming question. How come the Russian economy has actually doubled after the sanctions of the European Union? That means that the European Union and also the Euro-Atlantic community was not decisive enough to impose sanctions, to stick to them.

JURKONIS: Well, first of all, yes, the Kremlin has adapted to some of them. I mean, the sanctions are working, but we need to broaden, deepen and make sure that there’s no circumvention of sanctions. Obviously, when you have 30 countries it’s not easy. Also, if you block the way via Belarus or Central Asia, you know that there are some things going through Emirates, through China and all of that. Also, we need to admit that imposing sanctions, we are losing something, because there are certain costs of imposing sanctions, too.

At the end of the day, I want to say two things where the Kremlin has some advantage: unaccounted money, and brutal force. That’s what they have. And, whenever we are spending one penny, we need to account for the money. Whenever we would give the Moldovan government, say, 100,000 euro for some sort of reform or civil society, Russia can easily double, triple that because they are not accountable, they are stealing from their own people. It’s not that the Kremlin is much richer. They are much more unaccountable to their own people. That’s one.

The brutal force is that when you are not responsible to your own people, you can make really these stupid, insane decisions like the full-scale invasion against Ukraine, because anyone in Brussels, in Paris or Berlin, by saying we need to respond back, strike back, they understand the consequences of the war. They understand what is going to be the impact on its own population. And obviously, responsible governments, therefore, democratic governments are not prone to immediately go to war. But I think that in the long run, though, of course, Ukraine is paying a big, big price. We see that this solidarity with Ukraine is there, that this weapon supply is happening, the financial support aid is coming.

DERALLA: Lithuania is committing 1.43 percent of its GDP, which makes it the third country in the world, per GDP and per population is even higher, I would say.

JURKONIS: Because Lithuanians understand that Ukraine currently is fighting not only for themselves, but also for us, too. Because if Ukraine falls, then, you know, the Russians are going to go to the other country and maybe Baltic countries. So, it’s not only solidarity, it’s also a vital interest of ours. And we understand that Ukrainians are fighting for us as well.

DERALLA: And I will come to the last point here, also related to what you said before, that defending democracy means also defending Ukraine. So, what would victory for Ukraine mean? What would peace for Ukraine mean, according to you?

JURKONIS: Well, first of all, that all the Russian troops leave the territory of Ukraine. Obviously, Donbass, Crimea.

That is in the United Nations Charter, the territory should come back completely. Then, you know, reparations, because, if you ruined it, wiped out the entire city, you need to restore that. And we have the frozen assets of the Kremlin in Europe. These assets should go to restoring, rebuilding Ukraine. Obviously, we think, we assume that there is going to be an inevitable change in Russia, because the people of Russia would understand and would pay a heavy price for this criminal offense against Ukrainian people.

DERALLA: And against international law.

JURKONIS: As well. So, free and fair elections, democratic government. This is going to take years and years of change. But the immediate thing is to make sure that there are no Russian troops on the Ukrainian soil, that the international community is protecting Ukraine, is helping to restore Ukraine, and that all the Ukrainian people who were forced to flee are able to come back safely to their home and build the new, reformed, transparent Ukraine with the European path.

DERALLA: You’re certainly aware of the voices in the Euro-Atlantic community that are speaking about freezing the conflict as part of the path to the peace, which would also mean ceding part of Ukraine to Russia. What would you say, why is this so? And what would you tell them if you were able to deliver a message to these voices, to the carriers of these voices?

JURKONIS: I think that there’s a lack of determination, and also some level of cowardness. It’s a no-brainer. The UN Charter, international norms are saying that there shouldn’t be any foreign troops, it’s a violation of the national sovereignty and borders. So, I think that that’s the formula and the algorithm, and whoever says something against that, basically is jeopardizing the entire international system. So that’s one.

Second, I mean, if we talk about some sort of transitional solution, which is immediate – I’m lecturing Arts of Negotiation – I understand that there might be some interim solutions phases and all of that. There were a couple of suggestions voiced like that.

Some people think that you can make a deal with the devil, and there are books about bargaining with the devil, should you bargain. Nelson Mandela was saying that you can actually bargain with the devil, Winston Churchill said you cannot.

So, these are the two extremes. I think that the truth is somewhere in the middle, but at the end of the day, the ultimate goal is – no matter how long it will take, be it two years, five years, or ten – Ukraine should be whole and free, with Crimea, being able to control their borders, being able to protect their land, being able to rebuild their cities – like Mariupol – which were wiped out from ground.